Slavery--The Peculiar Institution

http://rs6.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aopart1.html

Part 1: The Atlantic Slave Trade | Liberation Strategies

During the course of the slave trade, millions of Africans became involuntary immigrants to the New World. Some African

captives resisted enslavement by fleeing from slave forts on the West African coast. Others mutinied on board slave trading

vessels, or cast themselves into the ocean. In the New World there were those who ran away from their owners, ran away

among the Indians, formed maroon societies, revolted, feigned sickness, or participated in work slow downs. Some sought

and succeeded in gaining liberty through various legal means such as "good service" to their masters, self-purchase, or

military service. Still others seemingly acquiesced and learned to survive in servitude.

The European, American, and African slave traders engaged in the lucrative trade in humans, and the politicians and

businessmen who supported them, did not intend to put into motion a chain of events that would motivate the captives and

their descendants to fight for full citizenship in the United States of America. But they did. When Thomas Jefferson penned

the words, "All men are created equal," he could not possibly have envisioned how literally his own slaves and others would

take his words. African Americans repeatedly questioned how their owners could consider themselves noble in their own

fight for independence from England while simultaneously believing that it was wrong for slaves to do the same.

This exhibit explores the methods used by Africans and their American-born descendants to resist enslavement, as well as to

demand emancipation and full participation in American society. Strategies varied, but the goal remained unchanged:

freedom and equality.

The Atlantic Slave Trade

"Roots Odyssey" By Romare Bearden

Twentieth-century artist Romare Bearden presents a stylized depiction of the odyssey of captives from Africa to the United

States. The ship shows the low decks that were constructed on slaving vessels so that the maximum number of African

captives could be transported. A black man's silhouette frames a view of the African continent, a U.S. flag, and seabirds

thought to symbolize the souls of Africans returning to their homeland.

One of the preeminent African American collage artists, Romare Bearden was born in Charlotte on September 2, 1914, lived

in Pittsburgh and Harlem, and died in New York on March 12, 1988. He was a 1935 graduate of New York University and

honored with many honorary degrees and awards, including the National Medal of Arts, awarded by President Ronald

Reagan in 1987.

Image: Caption follows

Romare Bearden. Roots Odyssey.

Screen print, 1976. 28 3/4 x 22 7/8.

Ben and Beatrice Goldstein Foundation Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6169.(1-10)

Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

The Geography Of The Atlantic Slave Trade

"Chart of the Sea Coasts of Europe, Africa, and America . . ."

From John Thornton, The Atlas Maritimus of the Sea Atlas.

London, ca. 1700.

Geography and Map Division. (1-11)

This map's elaborate cartouche (drawing), embellished with an elephant and two Africans, one holding an elephant tusk,

emphasizes the pivotal role of Africa in the Atlantic trading network. The South Atlantic trade network involved several

international routes. The best known of the triangular trades included the transportation of manufactured goods from

Europe to Africa, where they were traded for slaves. Slaves were then transported across the Atlantic--the infamous middle

passage--primarily to Brazil and the Caribbean, where they were sold. The final leg of this triangular trade brought tropical

products to Europe. In another variation, manufactured goods from colonial America were taken to West Africa; slaves were

carried to the Caribbean and Southern colonies; and sugar, molasses and other goods were returned to the home ports.

West Africa During The Eighteenth Century

During the 1700s when the Atlantic slave trade was flourishing, West Africans accounted for approximately two-thirds of

the African captives imported into the Americas. The coastal ports where these Africans were assembled, and from where

they were exported, are located on this mid-18th-century map extending from present-day Senegal and Gambia on the

northwest to Gabon on the southeast.

This decorated and colored map illustrates the dress, dwellings, and work of some Africans. The map also reflects the

international interest in the African trade by the use of Latin, French, and Dutch place names. Many of the ports are

identified as being controlled by the English (A for Anglorum), Dutch (H for Holland), Danish (D for Danorum), or French

(F).

Image: Caption follows

Guinea propia, nec non Nigritiae vel Terrae Nigrorum maxima pars . . . .

Nuremberg: Homann Hereditors, 1743.

Hand-colored, engraved map.

Geography and Map Division. (1-5)

Liberation Strategies

An Attempted Mutiny Aboard The Brigantine Hope

A slave revolt aboard the brigantine Hope, March 17, 1765.

Holograph transcript.

Peter Force Collection, Manuscript Division. (1-1)

Captured Africans often mutinied on board slave trading vessels. Rarely, however, did these attempts at liberation lead to

the Africans' return to their homelands. In this testimony William Priest discusses an unsuccessful mutiny of Africans on

board a Connecticut vessel en route to the United States from West Africa.

The captain, while trading for goods and slaves in Senegal and Gambia, experienced difficulties with some of his crew

members. He replaced several, beat others, and eventually, was himself murdered and thrown overboard by his crew. After

the captain's demise, the slaves rebelled, killed one crew member, and wounded several others before they were suppressed

after seven of them had been killed. Priest's testimony specifically relates to inquiries about the captain's death.

Denmark Vesey Slave Rebellion Plot Unveiled

Colonial and early national newspapers contain some actual accounts of slave insurrections, of small-scale slave uprisings,

and many rumors about them. This report details plans for an unsuccessful 1822 slave rebellion led by Denmark Vesey, a free

black man, around Charleston, South Carolina. Foiled in their efforts by slave informers, about thirty-five African Americans

were captured and hanged. However, the report states that "enough has been disclosed to satisfy every reasonable mind,

that considerable numbers were involved." One informer noted that Vesey told a meeting of the rebel group they would seize

the guard house and magazine to get arms. Then they would "rise up and fight against the whites for our liberties." Vesey

then read from the Bible about the deliverance of the children of Israel from Egyptian bondage.

Image: Caption follows

Lionel H. Kennedy and Thomas Parker.

An Official Report of The Trials of Sundry Negroes, Charged with an Attempt to Raise an Insurrection in the State of South

Carolina . . . .

Charleston, S.C.: James R. Schenck, 1822.

Rare Book and Special Collections Division. (1-6)

Walker's Appeal--a Call To Arms

Originally published in 1829 by David Walker, who was a second-hand clothing dealer in Boston, Massachusetts, this volume

was outlawed in many states because of its call for the violent overthrow of slavery. Walker, a native of Wilmington, N.C.,

was born September 28, 1785, of a free black mother and slave father. He advocated uncompromising resistance to slavery,

contending that African Americans should fight "in the glorious and heavenly cause of freedom and of God to be delivered

from the most wretched, abject and servile slavery. . ."

David Walker's Appeal in Four Articles, together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World . . . (September

1829).

Edited by Charles M. Wiltse.

New York: Hill and Wang, 1965.

General Collections. (1-18)

African Americans throughout the South got hold of Walker's Appeal, enraging Southern governments. Less than one year

after the publication of the Appeal, Walker was found dead of unknown causes. A $1,000 reward had been offered for his

death.

Nat Turner Slave Insurrection

During the 1831 uprising in Southampton, Virginia, led by Nat Turner, who was himself a slave, slave rebels systematically

went from house to house killing about sixty whites before they were disbanded. In the suppression of the revolt about one

hundred African Americans died and authorities hanged sixteen more.

In these confessions, Turner's lengthy autobiographical statement, he says that God led him to bring judgment against whites

because of the institution of slavery. He had a vision in which "white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun

was darkened--the thunder rolled in the heavens, and blood flowed in streams. . . ."

Image: Caption follows

The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia . . . .

Richmond: Thomas R. Gray, 1832.

Rare Book and Special Collections Division. (1-

Governor Of Virginia Discusses The Revolt

John Floyd, governor of Virginia, to James Hamilton, governor of South Carolina.

November 19, 1831.

Holograph letter.

Manuscript Division. (1-7)

James Hamilton, the governor of South Carolina, requested that Virginia governor John Floyd discuss the factors that led to

the Nat Turner revolt in Southampton, Virginia in 1831, the most well known slave revolt in U.S. history. About sixty white

people were killed. Governor Floyd's lengthy reply is in this letter.

Floyd blamed the "spirit of insubordination" on the "Yankee population" in general and Yankee peddlers and traders in

particular who shared Christianity with the slaves and taught them that all are born free and equal, and "that white people

rebelled against England to obtain freedom, so have blacks a right to do." Floyd placed the blame for masterminding the plan

on the church leaders, but he believed that all the discussions about freedom and equality led to the uprising.

Fear Of Slave Revolts

In addition to numerous published accounts documenting white fear of slave uprisings, many private letters discuss problems

brewing on individual plantations. In this letter, John Rutherford, an agent for Virginia plantation owner William B.

Randolph, wrote to Randolph indicating that a concerned neighbor near Randolph's Chatworth plantation feared "fatal

consequences" if the overseer did not cease his "brutality" toward the Chatworth slaves.

After the Chatworth overseer received a demanding letter of inquiry from Randolph, he answered on September 14, 1833,

stating that he had whipped some of the slaves because they were idle or had escaped. Although three escapees had not

returned, the situation was under control and work was proceeding as usual.

Image: Caption follows

John Rutherford to William B. Randolph on the slave mutiny at Chatworth, Richmond, Virginia.

September 1, 1833.

Manuscript Division. (1-9)

Sabotaging The Peculiar Institution

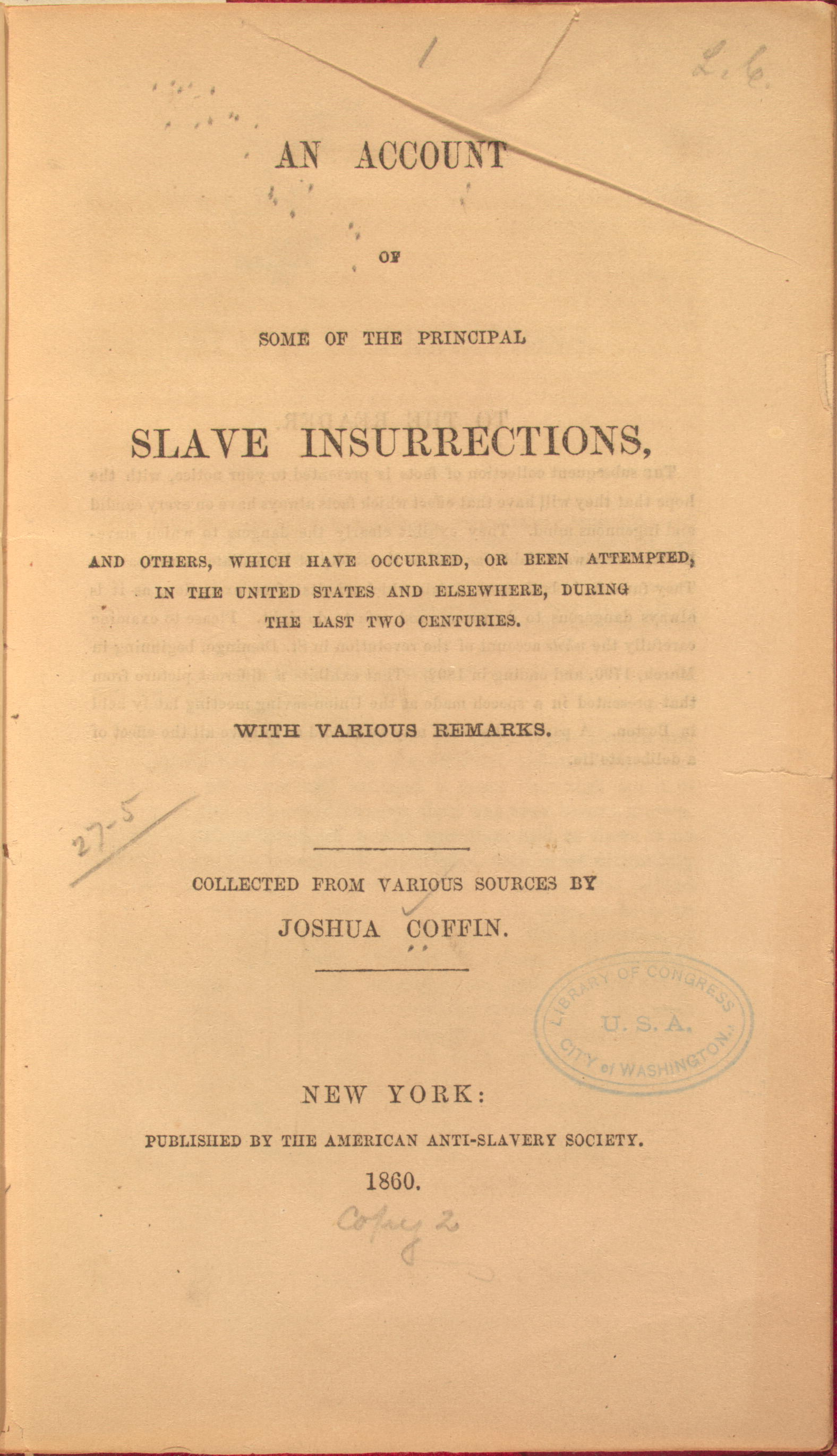

An Account of Some of the Principal Slave Insurrections . . . .

Compiled by Joshua Coffin.

New York: The American Anti-slavery Society, 1860.

Rare Book and Special Collections Division. (1-19)

Many abolitionists like Joshua Coffin argued that the existence of slavery in the United States constituted a real threat to

public peace and security. He used this volume to show how often slaves rose up against their owners to demand their

freedom. In it he describes slave resistance through large and small-scale rebellions in the North and South, work slow

downs, poisonings, arsons, and murders. He discusses many mutinies, including one on a Rhode Island ship when captives near

Cape Coast Castle (in present-day Ghana) rose and "murdered the captain and all the crew except the two mates, who swam

ashore."

Flights to Freedom

The Merchandise Of . . . Slaves, And Souls Of Men

The first captives came to the Western Hemisphere in the early 1500s. Twenty African slaves were brought to Jamestown,

Virginia, in 1619. A series of complex colonial laws began to relegate the status of Africans and their descendants to slavery.

The United States outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, but the domestic slave trade and illegal importation

continued for several decades.

This image depicts the miserable, cramped conditions of 510 Africans on board the bark Wildfire, who, while being

smuggled into the United States in 1860, were captured by an anti-slaving vessel. The slaves were taken to Key West,

Florida, and from there were sent to Liberia where the United States regularly repatriated "recaptured" Africans after

1808.

Image: Caption follows

"Africans on Board the Slave Bark Wildfire, April 30, 1860."

From Harper's Weekly, June 2, 1860.

Copyprint.

Prints and Photographs Division.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-19607 (1-20)